Every year, the feast-day of Saint Marcellus is celebrated in January; however, in the year 1362 there was no time for celebrating. For weeks, storms had been raging in the countries along the North Sea where the coastal communities feared for the worst and on the morning of the 16th of January, the day the festivities usually began, the weather was exceptionally bad. After a night of raging winds and heavy rainfall, the seawater level along the North Sea coast had risen by almost 2.5 meters. That day, high tides combined with the disastrous storm caused a storm surge that resulted in the flooding of vast areas of the Low Countries. An estimated 40,000 people perished and the events of that day are remembered as the Saint Marcellus Flood, or “de Eerste Grote Mandrenke”: the first great drowning of man.

In the late fourteenth-century storm surges and floods like the one in 1362 continuously battered the Low Countries. Due to the regional political turbulence known as the Hook and Cod wars (de Hoekse en Kabeljauwse twisten) the maintenance of dikes had been neglected, resulting in ever increasing damage and casualty among the coastal towns and communities. In 1404, the abbot of Ter Duin (in modern-day Belgium) writes about the disastrous flood on Saint Elisabeth’s day that it “(…) swept away houses, while animals and men drowned without mercy. The swollen sea swept over its banks in a way no-one has ever seen before”.

In the late fourteenth-century storm surges and floods like the one in 1362 continuously battered the Low Countries. Due to the regional political turbulence known as the Hook and Cod wars (de Hoekse en Kabeljauwse twisten) the maintenance of dikes had been neglected, resulting in ever increasing damage and casualty among the coastal towns and communities. In 1404, the abbot of Ter Duin (in modern-day Belgium) writes about the disastrous flood on Saint Elisabeth’s day that it “(…) swept away houses, while animals and men drowned without mercy. The swollen sea swept over its banks in a way no-one has ever seen before”.

Curiously, on this same feast-day of Saint Elisabeth in 1421 and 1424 two more disastrous floods occurred. During the Second Saint Elisabeth Flood of 1421, a total of 23 villages were swept away and around two-thousand people perished in the resulting chaos. This flood is famously depicted on the right panel of an altarpiece dedicated to Saint Elisabeth which is currently on display in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. On the right of the painting the water can be seen breaking through the dikes and engulfing the towns and villages.

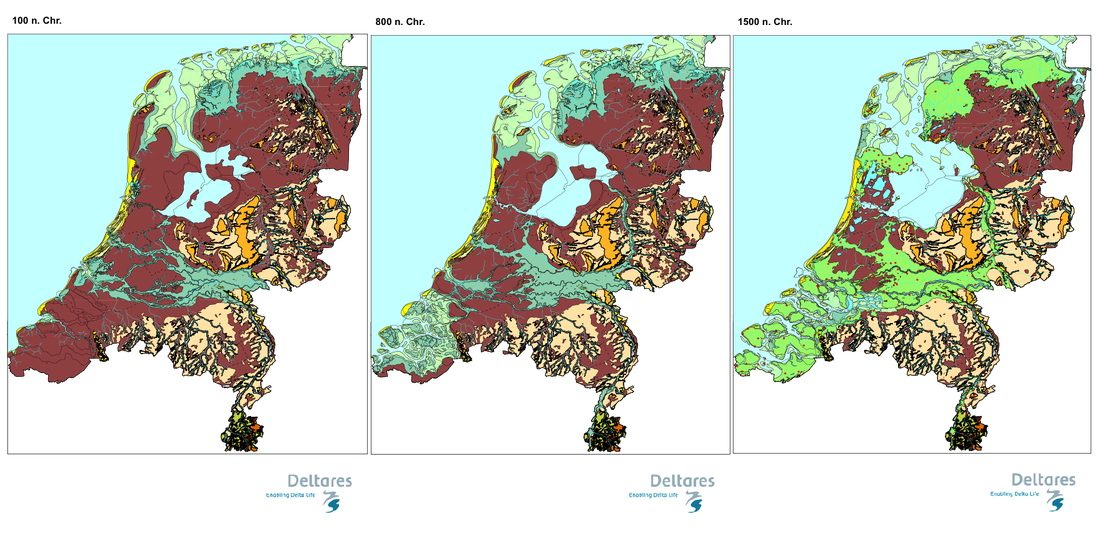

Nowadays, the bad weather in late mediaeval Northwestern Europe is usually explained by climatologists as the “little ice age”: the colder period after the Medieval Climatic Optimum. For hundreds of years, people in the Low Countries had been managing the water level in the peaty marshlands where they lived using primitive drainage systems. By digging channels parallel to each other in peat bogs or fens, the water would collect in these channels and the land in between the channels would become dry. Using a flap gate, a structure that is still used today, people were able to subsequently let the water flow out of the channels. In fact, the oldest flap gate discovered in the world was excavated in Vlaardingen, near Rotterdam in the Netherlands, and is dated to c. 70 - 120 AD. This system worked very well, but there was one big drawback. Peatland is 10% organic material and 90% water, thus by removing the water artificially, and lowering the groundwater level using these drainage channels, the peatlands started to subside. Apart from keeping everyone’s feet dry, dried peat, known as turf, was very widely used as fuel during this time. In a virtually treeless peatland, turf was the only fuel available. The practice known as peat cutting became more and more common and this resulted in huge peatlands virtually disappearing. Or - quite literally - going up in smoke. The extent of the problem becomes clear when looking at the palaeogeographic maps of the Netherlands.

Nowadays, the bad weather in late mediaeval Northwestern Europe is usually explained by climatologists as the “little ice age”: the colder period after the Medieval Climatic Optimum. For hundreds of years, people in the Low Countries had been managing the water level in the peaty marshlands where they lived using primitive drainage systems. By digging channels parallel to each other in peat bogs or fens, the water would collect in these channels and the land in between the channels would become dry. Using a flap gate, a structure that is still used today, people were able to subsequently let the water flow out of the channels. In fact, the oldest flap gate discovered in the world was excavated in Vlaardingen, near Rotterdam in the Netherlands, and is dated to c. 70 - 120 AD. This system worked very well, but there was one big drawback. Peatland is 10% organic material and 90% water, thus by removing the water artificially, and lowering the groundwater level using these drainage channels, the peatlands started to subside. Apart from keeping everyone’s feet dry, dried peat, known as turf, was very widely used as fuel during this time. In a virtually treeless peatland, turf was the only fuel available. The practice known as peat cutting became more and more common and this resulted in huge peatlands virtually disappearing. Or - quite literally - going up in smoke. The extent of the problem becomes clear when looking at the palaeogeographic maps of the Netherlands.

Almost 1400 years of drainage and peat cutting had left the landscape around 1500 AD looking like swiss cheese (or a dutch cheese, if you will). Storm surges and floods had taken their toll on the ever-subsiding landscape and what previously was peatland had now transformed into an area with huge lakes. Naturally draining the water and keeping villages and communities dry had become more and more difficult, and people started to develop methods of manual drainage. Devices such as scoop wheels driven by people or cattle were used, but it was all to no avail. The land continued to subside, and thus something had to be done to save the drowning Low Countries.

And then suddenly, in 1405, spectacular news arrived from the north of Holland. Two carpenters, Jan Grietenzoon and Floris van Alkemade had constructed a windmill that could “throw out” water. With this news, the members of the national water-management board (“Hoogheemraadschap”) could breathe a sigh of relief. As they prepare to make the journey north to witness “the miracle near the town of Alkmaar” with their own eyes, they wonder if this mysterious invention can save the flood-plagued country…

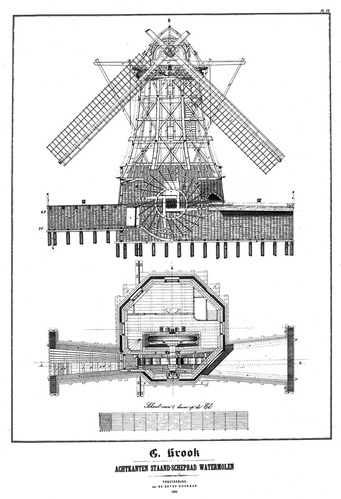

This event marks a major change in Dutch windmill technology. Since their appearance in the Low Countries in 1198, windmills were only used to grind cereals and no one had ever attempted to redesign them for another purpose. Thankfully, Jan Grietenzoon and Floris van Alkemade had thought to mount a scoop wheel to the sails of an existing flour mill and successfully made it pump water. The invention quickly spread, and waterpumping windmills (also called windpumps sometimes) were built everywhere. Suddenly, these large bodies of water that now filled up most of the map of Holland began to look less and less daunting. In 1533, the penny finally dropped. Two illustrious figures, Jan Jansz., bailiff of the Nieuwburg, and Willem Janz., the High Sheriff of Alkmaar, managed to pump the small Achtermeer lake dry, thus creating the first polder. After the successful drainage of the Achtermeer in 1533, the techniques quickly spread and the drainage of most of the large lakes began. A little side note on the nomenclature of polders is necessary here. In the Netherlands, we differentiate between polders that are areas of land where the water-table is artificially managed, and a droogmakerij (lit. “dry-makery"). It is these droogmakerijen that are the reclaimed pieces of land that are in English usually described as being ‘polders’.

The key feature of a droogmakerij was its clever use of windpower. By placing several windmills in a row, each a little higher than the previous one, and letting them pump the water upwards step by step over a much larger ‘head’ (the maximum height water can be raised with a pump).This novel idea, getrapte bemaling, would prove instrumental in the draining of larger and deeper lakes. As more of the smaller flooded areas of Holland were reclaimed, the very Dutch idea of trying to make money out of the practice started to emerge in the minds of Amsterdam’s rich merchant elite. In 1612, the large Beemster lake was successfully drained, under supervision of chief engineer and “king of the polders” Jan Adriaansz. Leeghwater, whose surname coincidentally means “empty water” in Dutch. The project was financed by Amsterdam’s wealthiest, and the soils of the reclaimed land proved to be very fertile and thus very profitable. More and more merchants started to buy large lakes and organized drainages, several of which turned out to be large failures. In the polder Heerhugowaard, that fell dry in 1633, the soils were found to be so poor that the merchants discussed flooding the whole area again and using it for fishing grounds, as it would be the only way they would be able to make money from the whole enterprise.

This event marks a major change in Dutch windmill technology. Since their appearance in the Low Countries in 1198, windmills were only used to grind cereals and no one had ever attempted to redesign them for another purpose. Thankfully, Jan Grietenzoon and Floris van Alkemade had thought to mount a scoop wheel to the sails of an existing flour mill and successfully made it pump water. The invention quickly spread, and waterpumping windmills (also called windpumps sometimes) were built everywhere. Suddenly, these large bodies of water that now filled up most of the map of Holland began to look less and less daunting. In 1533, the penny finally dropped. Two illustrious figures, Jan Jansz., bailiff of the Nieuwburg, and Willem Janz., the High Sheriff of Alkmaar, managed to pump the small Achtermeer lake dry, thus creating the first polder. After the successful drainage of the Achtermeer in 1533, the techniques quickly spread and the drainage of most of the large lakes began. A little side note on the nomenclature of polders is necessary here. In the Netherlands, we differentiate between polders that are areas of land where the water-table is artificially managed, and a droogmakerij (lit. “dry-makery"). It is these droogmakerijen that are the reclaimed pieces of land that are in English usually described as being ‘polders’.

The key feature of a droogmakerij was its clever use of windpower. By placing several windmills in a row, each a little higher than the previous one, and letting them pump the water upwards step by step over a much larger ‘head’ (the maximum height water can be raised with a pump).This novel idea, getrapte bemaling, would prove instrumental in the draining of larger and deeper lakes. As more of the smaller flooded areas of Holland were reclaimed, the very Dutch idea of trying to make money out of the practice started to emerge in the minds of Amsterdam’s rich merchant elite. In 1612, the large Beemster lake was successfully drained, under supervision of chief engineer and “king of the polders” Jan Adriaansz. Leeghwater, whose surname coincidentally means “empty water” in Dutch. The project was financed by Amsterdam’s wealthiest, and the soils of the reclaimed land proved to be very fertile and thus very profitable. More and more merchants started to buy large lakes and organized drainages, several of which turned out to be large failures. In the polder Heerhugowaard, that fell dry in 1633, the soils were found to be so poor that the merchants discussed flooding the whole area again and using it for fishing grounds, as it would be the only way they would be able to make money from the whole enterprise.

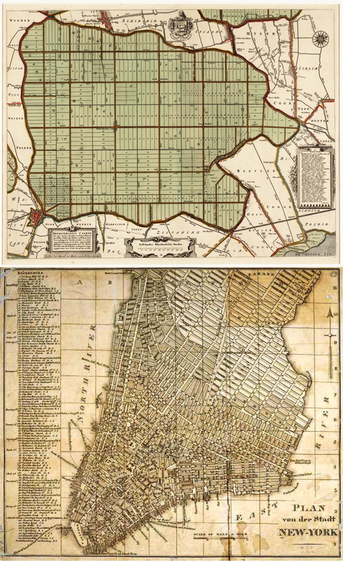

Top Map: Map of Beemster polder, north of Amsterdam Bottom Map: Map of Manhattan, New York

Top Map: Map of Beemster polder, north of Amsterdam Bottom Map: Map of Manhattan, New York Curiously, this notion of creating land also had an impact on the mindset of the Dutch. In modern-day Holland, we often joke with the sentence “god created the earth, and then the Dutch created Holland". A fine example of how they saw the reclaimed land as their own can still be seen in the road- and canal pattern of the Beemster polder, just north of Amsterdam. The whole polder is neatly divided in squares, with smaller blocks within each large square. It is worth noting the striking resemblance that the map of the Beemster bears with the street pattern of Manhattan, New York. New York City, of course, was founded by the Dutch as New Amsterdam in 1624. Could these two examples of ‘new land’ have a connection? We may never know, but it is curious indeed.

For centuries, the Dutch have been waging their war with the so-called Waterwolf. But it was in the “disaster year” of 1672 that they would first discover their experiences also brought about benefits. As the Dutch Republic was attacked by England, France, the Electorate of Cologne and the Bishopric of Münster (the latter two were states within the - then mighty - Holy Roman Empire), the Dutch’ centuries-long experience with managing water would prove to be a major advantage over their opponents. With French king Louis XIV’s armies approaching rapidly from the east, an almost 60 km (37 miles) long system of sluices and dikes were constructed as quickly as possible. This system could quickly flood vast areas of land, thus forming a large barrier of water between the enemy and the major province of Holland. After its successful deterring of the French troops, it remained in active service almost continuously as more forts and better sluice systems were built. In the early nineteenth century, the system was completely redesigned on the orders of king Willem I, and rebuilt so it also encompassed the city of Utrecht. The building of forts and waterways on this enormous project continued through much of the nineteenth century, and in 1880 a second system was designed, to further protect the city of Amsterdam from all sides. While the building was still very much under way, another event occurred that changed the world forever. World War I saw the first military use of airplanes, thus rendering the whole system of forts, canals, dikes and sluices virtually useless. The whole system however is today inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage list.

In more recent years, the waterwolf has become a peaceful neighbour for the Low Countries. After the catastrophic floods of 1953 and the subsequent building of one of the largest engineering projects in the world: the delta works, the Netherlands has been kept quite safe from flooding. Our most recent droogmakerij, the whole province of Flevoland, was reclaimed from the sea in 1968 and now houses almost 400,000 people. The Dutch, after centuries of experience dealing with the waterwolf, are now sought-after experts to help people all around the world with water-management. Dutch experts are currently involved in the artificial islands off the coast of Dubai, and after hurricane Katrina the Dutch have been helping rebuild and reengineer the levees of flood-stricken New Orleans. If only the French knew that ‘their’ colony is now being protected by the same technologies that once deterred them from attacking the Netherlands.

Although we now consider the waterwolf as an enemy of the past, rising seawater levels are in fact one of the biggest threats to the Netherlands. There is a saying in Dutch: “Wie water deert, die water keert”: he who daunts water, should deter water. With more than two-thirds of the country below sea level, it is of the utmost importance that we keep our rather wet history in our minds, and to keep weary of the waterwolf: our greatest friend and foe.

For centuries, the Dutch have been waging their war with the so-called Waterwolf. But it was in the “disaster year” of 1672 that they would first discover their experiences also brought about benefits. As the Dutch Republic was attacked by England, France, the Electorate of Cologne and the Bishopric of Münster (the latter two were states within the - then mighty - Holy Roman Empire), the Dutch’ centuries-long experience with managing water would prove to be a major advantage over their opponents. With French king Louis XIV’s armies approaching rapidly from the east, an almost 60 km (37 miles) long system of sluices and dikes were constructed as quickly as possible. This system could quickly flood vast areas of land, thus forming a large barrier of water between the enemy and the major province of Holland. After its successful deterring of the French troops, it remained in active service almost continuously as more forts and better sluice systems were built. In the early nineteenth century, the system was completely redesigned on the orders of king Willem I, and rebuilt so it also encompassed the city of Utrecht. The building of forts and waterways on this enormous project continued through much of the nineteenth century, and in 1880 a second system was designed, to further protect the city of Amsterdam from all sides. While the building was still very much under way, another event occurred that changed the world forever. World War I saw the first military use of airplanes, thus rendering the whole system of forts, canals, dikes and sluices virtually useless. The whole system however is today inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage list.

In more recent years, the waterwolf has become a peaceful neighbour for the Low Countries. After the catastrophic floods of 1953 and the subsequent building of one of the largest engineering projects in the world: the delta works, the Netherlands has been kept quite safe from flooding. Our most recent droogmakerij, the whole province of Flevoland, was reclaimed from the sea in 1968 and now houses almost 400,000 people. The Dutch, after centuries of experience dealing with the waterwolf, are now sought-after experts to help people all around the world with water-management. Dutch experts are currently involved in the artificial islands off the coast of Dubai, and after hurricane Katrina the Dutch have been helping rebuild and reengineer the levees of flood-stricken New Orleans. If only the French knew that ‘their’ colony is now being protected by the same technologies that once deterred them from attacking the Netherlands.

Although we now consider the waterwolf as an enemy of the past, rising seawater levels are in fact one of the biggest threats to the Netherlands. There is a saying in Dutch: “Wie water deert, die water keert”: he who daunts water, should deter water. With more than two-thirds of the country below sea level, it is of the utmost importance that we keep our rather wet history in our minds, and to keep weary of the waterwolf: our greatest friend and foe.

Author Bio

JIPPE KREUNING is windmiller and graduate student in biology and archaeobotany at the University of Amsterdam. After growing up in a windmill, he became the youngest certified windmiller of the Netherlands in 2011. His current academic work involves reconstructing past food patterns in the Netherlands using botanical remains from medieval cesspits and latrines. In 2014, he rediscovered the ruins of the 9th century horizontal windmills in north-eastern Iran and works regularly in Chalk-grinding mill d’Admiraal in Amsterdam.

Author contact: jippek[at]me[dot]com

Author contact: jippek[at]me[dot]com

RSS Feed

RSS Feed