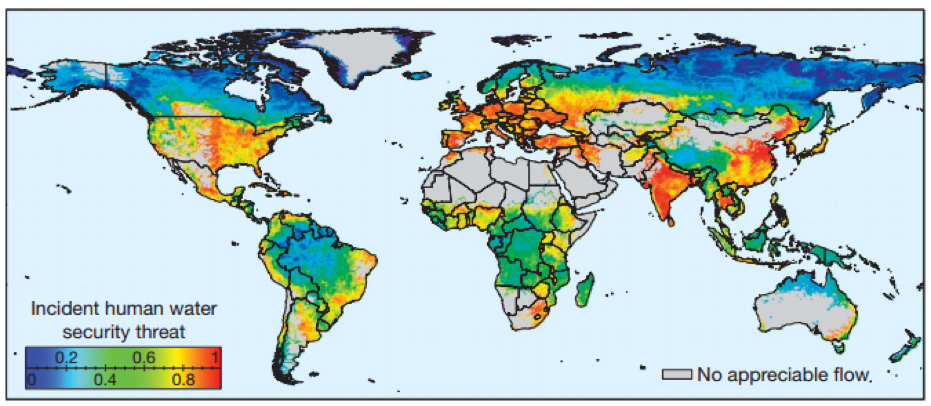

Figure 1 Global geography of incident threat to human water security (Vorosmarty et al., 2010).

Figure 1 Global geography of incident threat to human water security (Vorosmarty et al., 2010). Rivers have played a crucial role in many of mankind’s greatest milestones. Some of the earliest remains of hominid species were discovered around the Awash River in Ethiopia. Evidence of nomadic hunting to agriculture can be traced along rivers in the Near East. The first civilizations (approximately 3000 BC) were built around rivers Euphrates, Tigris, Nile and Indus, and a little later along the Yellow River. In addition to providing food and water for survival, rivers have also held a very spiritual meaning. Many cultures around the world have paralleled rivers to mothers and some cultures even believe that rivers have the power to cleanse humanity of its sins (McCully, 2001). We have used this abundance of water to make strides in human development however, we took our water for granted and now the state of rivers around the world is in turmoil.

A study titled, “Global threats to human water security and river biodiversity” published in Nature in 2010, states that nearly 80% of the world’s population is exposed to high levels of threat to water security. The study focused on rivers and concluded that drivers such as catchment disturbance, pollution, water resource development and biotic factors are the causes to such threats. The figure below shows the global incident threat to human water security quantified by using a global geospatial framework and merging individual stressors.

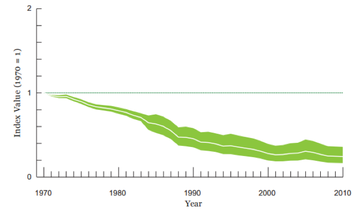

Figure 2: Freshwater LPI (1970 - 2010) based on trends in 3066 populations of 757 mammal, bird, reptile, amphibian and fish species. The green band shows the confidence limits of the data (WWF, 2014).

Figure 2: Freshwater LPI (1970 - 2010) based on trends in 3066 populations of 757 mammal, bird, reptile, amphibian and fish species. The green band shows the confidence limits of the data (WWF, 2014). Human water security is only one half of the picture because freshwater species are also in critical condition. The 2014 WWF Living Planet Report has established a living planet index (LPI) that reflects changes in the state of the planet’s biodiversity by using trends in population sizes of vertebrate species to calculate average changes of abundance over time. The figure below shows that the freshwater LPI from 1970 to 2010 (1970 LPI = 1) has declined by 76%.

There is an alarming cause for concern for humans and wildlife due to the state of rivers worldwide. I now want to shift your attention to Canada. As a mostly uninhabited land mass, Canada has not yet done nearly as much damage to our rivers as some parts of the world shown in Figure 1. But Canadian rivers are not immune to the potential threats that have taken hold on the rest of the planet. A report titled, “Canada’s rivers at risk” by WWF published in 2011 outlined the three main challenges to Canada’s rivers:

The challenge for Canada, as one of the world’s water-wealthy nations, is to protect and restore the nation’s rivers while playing a leading role in feeding and fuelling an increasingly thirsty and warming world.

As a Master’s student studying civil engineering, I’m taking the opportunity to make a difference in how Canadians value our rivers. Our team of interdisciplinary researchers at Queen’s University is investigating the potential impacts of oil spills to fish habitats in Canadian rivers. This study will help outline the environmental and economic benefits/drawbacks of the thousands of kilometers of proposed oil pipelines that will cross numerous waterways with the potential to spill oil directly into the freshwater and freshwater sediments. We are developing a framework that will help future industry and government agencies make responsible choices when it comes to our rivers in order to prevent Canada from becoming the next red-shaded area in Figure 1.

- Flow regulation and fragmentation – Thousands of dams have disturbed natural flow paths and stored water that would naturally flow downstream freely.

- Withdrawals and diversion – Moving water between watersheds artificially causes changes in river flow, which can have many negative consequences.

- Climate change – Maximum flow rates are generally decreasing in rivers, while spring runoff is occurring earlier. Climate change can also alter intensity, duration and frequency of flooding.

The challenge for Canada, as one of the world’s water-wealthy nations, is to protect and restore the nation’s rivers while playing a leading role in feeding and fuelling an increasingly thirsty and warming world.

As a Master’s student studying civil engineering, I’m taking the opportunity to make a difference in how Canadians value our rivers. Our team of interdisciplinary researchers at Queen’s University is investigating the potential impacts of oil spills to fish habitats in Canadian rivers. This study will help outline the environmental and economic benefits/drawbacks of the thousands of kilometers of proposed oil pipelines that will cross numerous waterways with the potential to spill oil directly into the freshwater and freshwater sediments. We are developing a framework that will help future industry and government agencies make responsible choices when it comes to our rivers in order to prevent Canada from becoming the next red-shaded area in Figure 1.

References

1) McCully, Patrick. "Silenced Rivers: the Ecololgy and Politics of Large Dams." (1998).

2) Vörösmarty, Charles J., et al. "Global threats to human water security and river biodiversity."

Nature 467.7315 (2010): 555-561.

3) WWF. “Living planet: Report 2014.” WWF, 2014.

4) WWF. “Canada’s Rivers at Risk.” WWF, 2011.

1) McCully, Patrick. "Silenced Rivers: the Ecololgy and Politics of Large Dams." (1998).

2) Vörösmarty, Charles J., et al. "Global threats to human water security and river biodiversity."

Nature 467.7315 (2010): 555-561.

3) WWF. “Living planet: Report 2014.” WWF, 2014.

4) WWF. “Canada’s Rivers at Risk.” WWF, 2011.

About the Author

Avneet Button is in the second year of his Master's in Civil Engineering at Queen's University. In addition to his research, Avneet enjoys serving as the Industry Finance Manager for WatIF 2016. After completion of his Master's, Avneet aims to tackle large scale water resource engineering projects in efficient, environmentally sustainable and cost effective methods.

Author Contact:

14ab28[at]queensu[dot]ca

Author Contact:

14ab28[at]queensu[dot]ca

RSS Feed

RSS Feed